In this Market Pulse, Chief Property Economist Kelvin Davidson explores the importance of higher yields for property investors, looking at where those yields are and which property types might look the most appealing.

Over the next few years, capital gains may well be harder to come by for property investors, which means the ‘nuts and bolts’ are likely to become more important – a focus on cost control, pushing up rents if they can, and perhaps most importantly for new buyers, getting the properties with the highest yields (for acceptable risk). But where are those yields and which property types might look the most appealing?

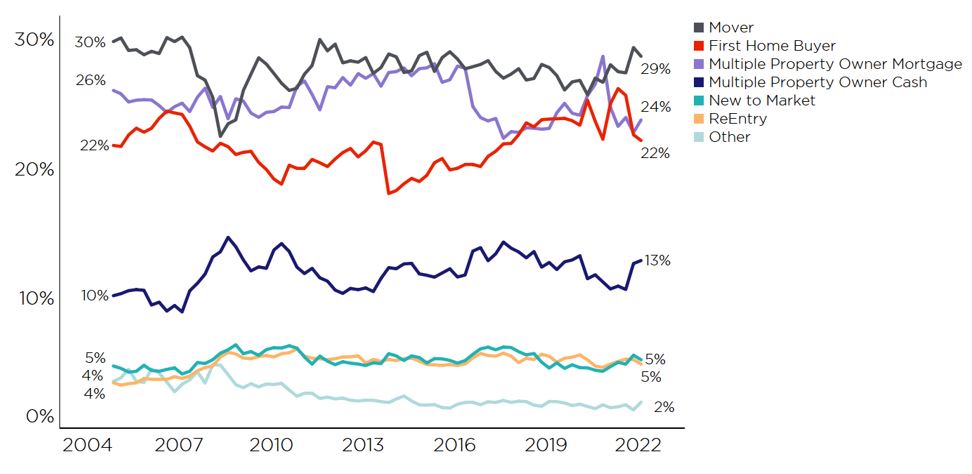

Our Buyer Classification data shows that mortgaged multiple property owners, typically a genuine investor, have seen their market share of purchases fall over the past year or so, but at 23-24% they certainly haven’t abandoned property altogether (see the first chart). There is still investment going on, with new-builds clearly an option, given the ability to keep claiming mortgage interest deductions from tax, as well as their exemption from the 40% deposit requirement under the loan to value ratio rules.

Chart 1. NZ % share of property purchases (Source: CoreLogic)

Similarly, it’s also worth noting that we’re not seeing any real signs of existing investors selling properties at a faster rate, with the Brightline Test potentially a limiting factor here, but also that those that have been in the market a while tend to have smaller mortgages and therefore be less affected by higher interest rates.

However, average property values are now falling steadily, and if the 2008-09 financial crisis is anything to go by, even after we’ve reached the bottom, it could be a number of years until we regain the recent peak for the level of house prices. In other words, the next 4-5 years could be a pretty quiet time for capital gains.

In addition, it’s obviously become more complicated (and costlier) to be a landlord, given changes such as Healthy Homes legislation and the extra difficulty in removing a troublesome tenant. On top of that, of course, mortgage rates have risen sharply, and although an interest-only loan can reduce the servicing payments for the first year or two, clearly no principle is being paid off, and the property may well require a top-up out of other income anyway.

To be fair, one silver lining from an investor’s perspective (not for tenants though) is that rents continue to rise at around 6-7% annually, double the long-term pace. But given that tenants’ wages ultimately cap how much they can afford to pay, there’s a limit to how long such rapid rates of rental growth can last.

Overall then, in this environment, it would be no surprise to see investors focusing on yield, i.e. trying to buy properties that have the highest rent in relation to their purchase price (albeit still within the investor’s tolerance for risk). So how do yields look around NZ, and also split by property type and bedroom count?

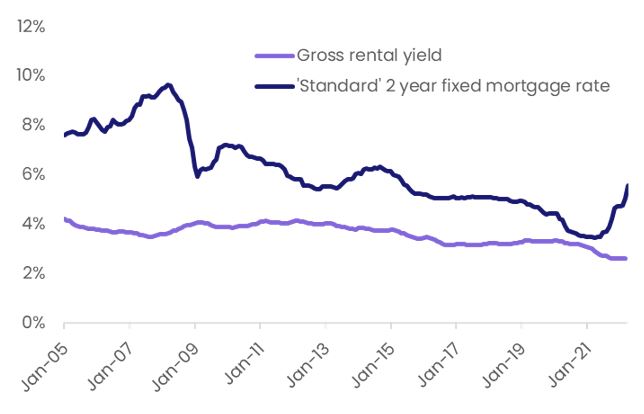

Starting with the general context, the national average gross property yield is currently now just 2.6%, versus the average ‘standard’ two-year fixed mortgage rate (RBNZ aggregated data) of 5.6% (see the second chart). That negative yield gap (-3%) is the largest since mid-2010, or in other words the least favourable position for property yields versus mortgage costs for more than a decade, after a period in 2020-21 where it was very beneficial for investors. It’s also worth noting that term deposit rates for durations of at least a year are now generally back at 3% or more, and flows of money into term deposits have started to pick up again (after previous outflows).

Chart 2. NZ average gross rental yields and mortgage rates (Sources: CoreLogic, MBIE, RBNZ)

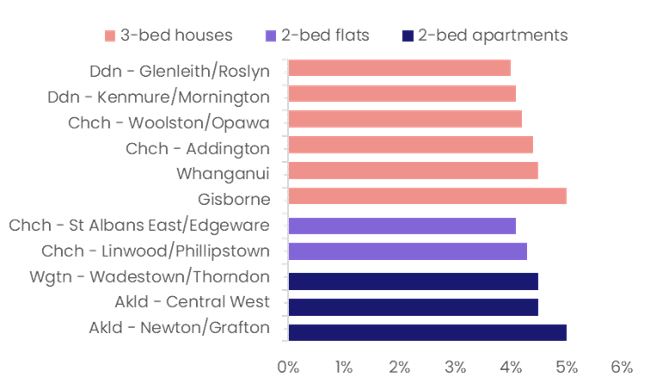

Drilling down to property type and location, and starting with apartments (and a minimum threshold for number of properties), for a fairly typical two-bedroom property there are still a few areas with gross yields of at least 4.5% – such as Auckland’s Newton/Grafton and Central West, and Wadestown/Thorndon in Wellington. For two bedroom flats, for example, some parts of Christchurch still have yields of at least 4%. Then in the largest category – three bedroom houses – again yields of 4% or more are still conceivable in parts of the main centres (e.g. Christchurch and Dunedin), as well as Gisborne and Whanganui amongst the next tier of towns/cities (see the third chart).

Chart 3. Gross rental yields by property type/location (Sources: MBIE, CoreLogic)

Of course, at the other end of the spectrum, there are some very low yields in the market. For example, three-bedroom houses are sub-2% around a number of Auckland suburbs, such as Remuera, Westmere/Surrey Crescent, St Heliers/Glendowie, and Grey Lynn/Arch Hill, all at 1.7%.

All in all, there are always likely to be ‘bargains’ out there for investors in any market conditions, especially if they get a discounted purchase price or are skilled in renovations, as examples. Many investors would tell you that in fact a downturn is the best time to be buying. And no doubt would-be investors will be breathing a little easier on the back of the Reserve Bank’s decision to push out any formal caps on debt to income ratios until at least mid-2023, and even then only if required.

However, all that said, some of the key drivers of returns in recent years (e.g. strong capital gains and positive monthly cashflow, especially over 2020-21) have been dramatically reduced, and the economics of investment certainly look likely to be trickier over the next few years. Cost control and a focus on buying high-yield properties (for the lowest risk) seem to be pretty good ideas.

Of course, for existing landlords who have held property for longer, the pressure will be less acute. However, it still wouldn’t be the biggest surprise if we started to see a few more listings come through from existing investors (if they’re outside their Brightline period) in the medium term. After all, hanging in for long-term capital gains is one thing, but sustaining cash losses on a yearly basis in the meantime may not be palatable for some investors for too long – especially given the loss ring-fencing rules too.