Mortgage lending activity was higher in August than a year ago – the first annual rise for about two years. Part of this early-stage recovery relates to the loosening in the loan to value ratio rules from 1st June. Looking ahead, more growth in lending activity (and property sales volumes and house prices) seems likely, but it might still be fairly subdued by past standards.

The latest data from the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) showed that there was $5.8bn of gross mortgage lending activity in August, up by $0.4bn from a year ago. This is the first annual rise in lending volumes since August 2021. (These figures cover new loans, top-ups, and bank switches, but not existing loans that are being repriced).

Within that overall total, the breakdown of the figures showed that owner-occupiers borrowed more this August than the same month last year, but investors were on a par with a year ago. That softer performance from investors is hardly surprising, given the cashflow pressures on an investment purchase that are currently arising from low gross rental yields and high mortgage rates.

Meanwhile, interest-only lending remains ‘under control’, with about 36% of loans to investors in August being done on this basis (compared to a cyclical peak of 46% in July/August last year) and a figure of only about 14% for owner-occupiers, compared to around 20% a year ago.

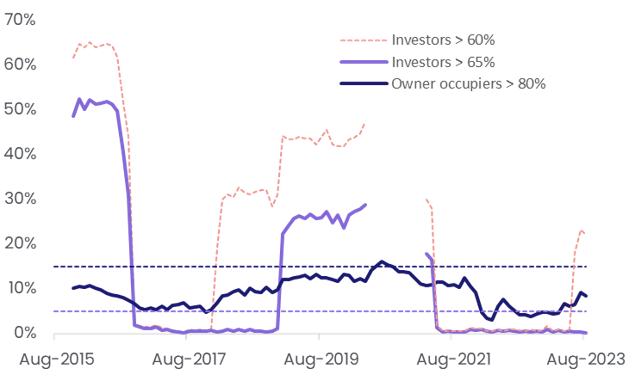

Perhaps the most interesting cut of these figures, however, is still the breakdown by loan to value ratio (LVR), which showed that lending to investors who don’t have the required 35% deposit (unless going new-build) remains almost non-existent. By contrast, given the relaxation of the LVR rules from 1st June, the past few months have shown a sharp rise in the share of lending to investors with a 35-40% deposit (see the first chart) – a group precluded by the previous LVR settings.

1. % of lending at high LVR (Source: RBNZ)

Of course, it’s also worth reiterating that overall investor lending flows remain subdued, and that their purchasing activity in the market is also still fairly muted. In other words, those investors borrowing with a 35-40% deposit (or 60-65% LVR) may be topping up existing loans or switching banks, rather than actively buying more properties.

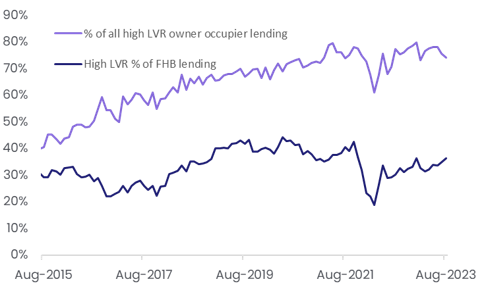

Similarly, low-deposit lending to owner-occupiers has also risen lately, from around 6% of activity in May to 8-9% now – still below the (new) 15% speed limit, but nevertheless the highest share since late 2021. In turn, a high share (around 75%) of those low-deposit flows for owner-occupiers is actually absorbed by first home buyers (see the second chart).

2. High LVR lending to first home buyers (Source: RBNZ)

In addition, today’s release from the RBNZ also contained the latest update to the newly-published breakdown covering ‘loan purpose’ – i.e. to purchase a property, switch banks, or top up an existing loan. These figures showed that top-ups and bank switches have remained relatively stable in the past few months, but house purchase loans are showing early signs of an upturn.

Overall, then, it’s early days, but the latest mortgage lending figures add to other evidence that the housing market downturn has (all but) ended, helped in part by the loosening of the LVR rules from 1st June, and also relaxed CCCFA rules one month prior to that.

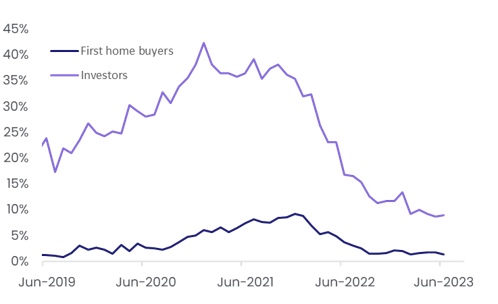

However, we’re cautious about the speed and scale of any near-term rebound in property sales, lending volumes, or house prices. After all, mortgage rates aren’t likely to fall significantly anytime soon (maybe not for at least another year) and the serviceability test rates certainly remain a key hurdle for many would-be borrowers at present. Indeed, high mortgage rates have recently been a key factor limiting the size of loans in relation to incomes (see the third chart), given they restrict how much debt that can actually be serviced from a given wage.

3. % of lending at DTI >7 (Source: RBNZ)

On that note, we still think there’s a reasonable chance that formal caps on debt to income (DTI) ratios will be imposed by the RBNZ in 2024. To be fair, given that high DTI lending has already fallen, formal caps may not actually do much straightaway. But if imposed, they’d mean the RBNZ is already ‘ahead of the curve’ for when interest rates do eventually fall again and possible financial stability risks from larger new mortgages re-emerge.

In the long run, DTIs would tend to tie house prices more closely to incomes (which grow slower than the historical rate of house price inflation we’ve seen in NZ over the past 20-30 years), and also limit the number of properties that anybody can own until there’s been sufficient time (maybe five to seven years) for their incomes to grow enough to allow the next purchase.